Apprehended bias and judicial independence

The High Court has unanimously held that communications and other contact between the trial judge and barristers for one of the parties appearing before the trial judge should not have occurred and gave rise to an apprehension of bias. In so holding, the High Court restated the importance of judicial independence and of the apprehension of bias principle.

Background

The appellant (the husband) and the first respondent (the wife) married in 1979 and separated in 2005. In 2006, the appellant commenced proceedings pursuant to s 79 of Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) (Act) for property settlement orders. In 2011, Crisford J of the Family Court of Western Australia made orders for the settlement of property which divided the net assets of the parties which included, inter alia, orders providing for the early vesting of an identified trust. The orders also included ‘the Early Vesting Orders’ which required a payment of $338,000 to the appellant's mother, who was a general beneficiary of the trust prior to the distribution of the trust fund.

The Full Court of the Family Court of Western Australia set aside the Early Vesting Orders in 2013 but did not make any consequential orders, whether remitting that issue for rehearing or otherwise. In 2015, Walters J of the Family Court of Western Australia held that the property settlement orders made in 2011 were not final orders and the Court retained power to make orders under s 79 of the Act. The trial of the remaining issues commenced on 3 August 2016 and oral submissions occurred on 13 September 2016. Some 17 months later, on 12 February 2018, Walters J made property orders under s 79 of the Act, but those orders did not set aside or vary the 2011 property orders and were inconsistent with them. Walters J retired three days after the delivery of his judgment.

On 9 September 2016, prior to oral submissions, the corporate trustee and the husband’s mother (Additional Parties) had relied on ten statements and rulings made by Walters J during the trial in applying for his Honour to recuse himself on the ground of apprehended bias, (First Recusal Application). On 13 September 2016, his Honour delivered ex tempore dismissing the First Recusal Application.

In May 2018, the appellant’s solicitor wrote to the first respondent’s barrister raising concerns that the barrister had had undisclosed personal dealings with Walters J during the proceedings. In response, the barrister disclosed that between March 2016 and February 2018, she had met the judge for a drink or coffee on approximately four occasions, had spoken with him by telephone on five occasions and exchanged numerous text messages with him but not during the evidence stage of the trial. The barrister said that those communications did not concern the substance of the matter.

The appellant appealed to the Full Court of the Family Court of Western Australia on the following two grounds:

- whether the property orders made in 2018 should be set aside on the ground of reasonable apprehension of bias; and

- whether the power in s 79 of the Act could be exercised by Walters J when Crisford J had already made property orders in 2011.

The majority of the Full Court dismissed the appeal on both grounds. The appellant appealed to the High Court raising the same issues.

The High Court allowed the appeal in a unanimous decision of Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon and Gleeson JJ.

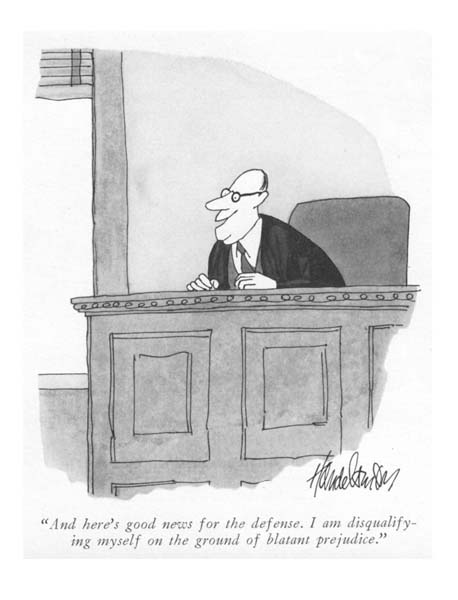

What is apprehension of bias and judicial independence?

The High Court referred to the well-established principles of judicial independence and impartiality, in particular as in set out in Ebner v Official Trustee in Bankruptcy (2000) 205 CLR 337. Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon and Gleeson JJ noted the principle that ‘justice should both be done and be seen to be done’ and that the apprehension of bias principle is that ‘a judge is disqualified if a fair-minded lay observer might reasonably apprehend that the judge might not bring an impartial mind to the resolution of the question the judge is required to decide’(at [11]).

Their Honours reiterated the position in Ebner that the application for apprehension of bias requires two steps (at [11]):

- ‘the identification of what it is said might lead a judge ... to decide a case other than on its legal and factual merits’; and

- there must be articulated a ‘logical connection’ between that matter and the feared departure from the judge deciding the case on its merits.

The High Court also noted what had been said in Johnson v Johnson (2000) 201 CLR 488, namely, that the reasonableness of the alleged apprehension of bias could be assessed once these two steps were taken and ‘is to be considered in the context of ordinary judicial practice’. The fair-minded lay observer does not have to have ‘a detailed knowledge of the law, or of the character or ability of a particular judge’ (at [12]).

Their Honours said, further, that ordinary judicial practice is that after the commencement of the trial there should be ‘no communication or association’ between the judge and one of the parties or the legal advisers or witnesses of such a party otherwise than in the presence of or with the previous knowledge and consent of the other party. Further, if an act or conduct is carried out in a way which affords a reasonable basis for suspicion, confidence in the impartiality of the judicial officer would be diminished (at [13]).

Application

Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon and Gleeson JJ held that in the circumstances of this case, the communications between Walters J and the barrister took place in the absence of and without the knowledge and consent of the other parties (at [14]). A fair-minded lay observer familiar with basic judicial practice, would reasonably apprehend that Walters J might not bring an impartial mind to the resolution of the questions his Honour was required to decide (at [15]). Therefore, those communications should not have occurred as there were no exceptional circumstances (at [14]).

The High Court held that there was a ‘logical and direct connection between the communications and the feared departure from the trial judge deciding the case on its merits’ (at [15]). Walters J’s impartiality might have been compromised by some aspect of the personal relationship with the barrister or something said in the communications (at [15]).

The High Court stated that the reasoning of the Full Court was erroneous in the following respects:

- the conclusion that Walters J was aware of some of his obligations by pausing the communications with the wife’s barrister during the course of the trial and might have failed to appreciate that the same rigidity applied at other times. The fair-minded observer would understand that his Honour mistakenly held such a view but would not consider his lack of disclosure to be sinister (at [18]); and

- that the second limb in Ebner was not made out because a fair-minded observer would accept that the trial judge and the barrister would adhere to professional constraint in what was discussed and would accept that a professional judge who has taken an oath would not discuss the matter at hand (at [20]).

In relation to the first error of the Full Court, the High Court held that the perceptions of independence and impartiality was so important ‘that even the appearance of departure from it is prohibited lest the integrity of the judicial system be undermined’ (at [18]). In deciding an application for apprehension of bias, a court was not to predict whether a judge might not bring an impartial mind to bear or question the understanding or motivation of a judge (at [18]).

With respect to the second error of the Full Court, the High Court held that ‘the alignment of the fair-minded lay observer with the judiciary and the legal profession is inconsistent with the apprehension of bias principle and its operation and purpose’. The hypothetical observer is not postulated as a lawyer but ‘a member of the public served by the courts’ (at [21]).

The High Court further stated that the lack of disclosure in this case was very concerning as the trial judge failed to appreciate the need to disclose the communications, especially where he had to deal with the First Recusal Application made by the Additional Parties on other grounds. This would make a fair-minded lay observer reasonably doubt the correctness of the wife’s barrister’s claim that the communications did not concern ‘the substance of the case’ (at [19]).

In addition, Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon and Gleeson JJ concluded that the 2011 property orders, without the Early Vesting Orders, had not been set aside, as the power under s 79 to deal with the property had been exercised and was exhausted by Crisford J in making those orders. Contrary to the view reached by the Full Court, the High Court held that s 79 power in relation to the Early Vesting Orders was not spent as the Full Court did not deal with the re-exercise of the power under that section or remit them for further hearing.

Therefore, the High Court allowed the appeal and remitted the matter for rehearing before a single judge of the Family Court of Western Australia.