The Fragility of the Rule of Law in Hong Kong

The Western liberal concept of the rule of law is under attack in Hong Kong.1 On 30 June 2020, the central government in Beijing, using the blunt instrument of the National Security Law (NSL), made a deep and ragged incision into the body-politic aimed at suppressing political enemies of the central government, in particular, democracy ‘activists’ exercising the civil rights guaranteed to them under the Basic Law. Ironically, it was a fatal contradiction within the Basic Law that enabled that to happen.2

The rule of law is a fragile concept that requires regular defending. The Hong Kong Bar Association (HKBA) has consistently taken a principled stance in defending attacks on the rule of law which have occurred with increasing frequency in recent years. In response it has been threatened with government intervention.

The NSL creates four classes of criminal offence: secession; subversion; terrorist acts; and colluding with foreign forces. It operates with little regard to the separation of powers, judicial independence, due process and equality before the law. The HKBA has drawn particular attention to the following aspects:

- the power of interpretation is vested in the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress;

- the Chief Executive is to designate an approved list of judges to hear NSL cases, with the power to remove such judges whose words or deeds endanger national security;

- the central authorities can decide to exercise jurisdiction in a given case for suspects to be removed to mainland China for criminal trial in accordance with mainland criminal procedures, without any judicial oversight of the exercise of that executive power by the local jurisdiction;

- National Security Agency personnel are not subject to local jurisdiction when exercising their duties in accordance with the NSL;

- extraordinary powers are granted to the Special National Police Unit and covert surveillance is permitted without judicial controls;

- presumption of bail is reversed, mandatory minimum sentences are prescribed which remove judicial discretion, and the Secretary for Justice is empowered to deny trial by jury without any residual judicial discretion;

- the newly established National Security Council is exempt from judicial review.3

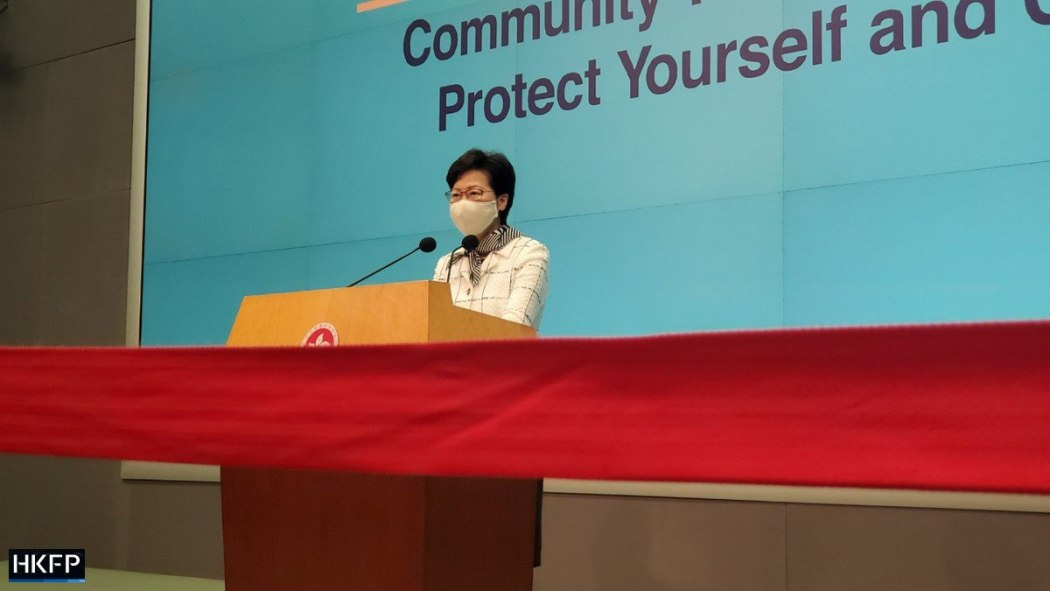

On 1 September 2020, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong publicly commented that the separation of powers does not exist in Hong Kong and that to hold a contrary view was, ‘erroneous’.4 She said that an executive-led system of governance operated in Hong Kong, by reason of the fact that administrative, legislative and judicial powers are ultimately accountable to the central government in Beijing. Her comments were in support of a decision to delete the phrase ‘separation of powers’ from Liberal Studies textbooks after screening by Beijing’s Education Bureau.

On 2 September 2020, the former Chief Justice of New South Wales, James Spiegelman, tendered his resignation as a non-permanent judge of the Court of Final Appeal of Hong Kong. His stated reasons for doing so, ‘related to the content of the national security legislation’.5

On that same day, the HKBA released a press statement challenging the Chief Executive’s view that there is no separation of powers in Hong Kong, citing judicial authority, public statements of two former chief justices, as well as the Basic Law’s structure and provisions. The HKBA gave a thorough rebuttal of the following premises in the Chief Executive’s comment:

- That the HKSAR derives its authority from the Central Peoples’ Government (CPG) and it is the office of the Chief Executive which is directly accountable to the CPG; and

- the courts deal with legal issues but not political issues, the latter being matters for the executive or the legislative authorities. 6

Hong Kong Bar Association, 2021.

Those premises are notable because they closely align with the concept of the rule of law promulgated by the central government.

The second premise touches upon the justification for sovereign dictatorship elaborated by the constitutional lawyer, Carl Schmitt, adapted for application to China’s situation by influential Chinese legal scholars, a point I return to below. At present it is sufficient to note that in 1932, Schmitt argued in the Constitutional Court of Germany on behalf of the Federal government (with partial success) that the Court lacked jurisdiction to decide the legality of executive measures taken during the ‘Prussian Coup’ because such measures were political in nature.7

As to the first premise and the existence of the separation of powers, official government policy has been adopted which casts new light on the issue, namely, the ‘Plan on Building the Rule of Law in China (2020–2025)’ (the Plan).8 Two key aspects of the Plan are, ‘Xi Jinping Thought on the Rule of Law’, and the development of, ‘socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics’. The core elements of the former are strengthening the CCP’s centralised and unified leadership, ‘scientific legislation’, strict law enforcement, fair trials and a law-abiding population.

Under the Chinese Constitution, ‘the defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics is the leadership of the CCP’ (Article 1).9 Moritz Rudolf explains that this ties in with ‘socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics’, as follows:

'The CPC’s leadership is propagated as the most fundamental guarantee of the rule of law in the PRC. According to Marxist legal tradition, Beijing sees law primarily as an instrument of the CPC. After the communist revolution, the law was subjected to 'the people', and only the CPC has the legitimacy to interpret their will.'10

Since CCP leadership is the most fundamental guarantee of the rule of law and the CCP is above the State, there is no constitutional justification for importing a foreign concept of separation of powers into ‘socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics’. Put bluntly:

'… the party-state leadership rejects an independent judiciary and the principle of separation of powers as ‘erroneous western thought’.'11

Rudolf concludes that the Plan:

'…bears no resemblance to the Western understanding of the rule of law. Its objective is for the law to better control state actions, but without limiting the power of the party in any way. Instead, the law is to become a more efficient instrument of rule for the party.'12

In that way, the Plan resembles what John Keane has described as the ‘phantom rule of law’ used by despotic regimes to cloak the exercise of arbitrary power with legal legitimacy:

'…. when power-hungry despots publicly bathe in the waters of legal reasoning and legal quarrels structured by their own legal codes.'13

The NSL is consistent with a constitutional order which privileges executive decision-making and insulates it from judicial review and democratic accountability. In short, a form of sovereign dictatorship. For example, in relation to the arrests of fifty-three pro-democracy candidates in January 2021 for alleged ‘subversion’ by participating in election primaries, Ryan Mitchell14 has observed:

'The use of the NSL to prosecute many of the participants in the July 2020 ‘pro-democracy Primaries’, construing an electoral process as a fundamental threat to political order, marks the law’s most important use so far to generally transform the overall political environment.'15

Australia’s Foreign Minister, Marise Payne, reacted to the news of the arrests, stating:

'Australia has consistently expressed concern that the National Security Law is eroding Hong Kong’s autonomy, democratic principles and rule of law.'16

Mitchell discusses the contributions of Chinese constitutional scholars in developing Schmitt’s theories for application to China’s circumstances, most recently, his theory of sovereign dictatorship.17 In particular, the recent emphasis by Chen Duanhong on the importance of the sovereign’s friend/ enemy decision which subordinates individual freedoms and the rule of law to national security. As Mitchell points out, Chen’s conception of the sovereign power of the CCP:

'… should not be understood to be 'limited' by mediating factors such as Hong Kong’s common law judiciary (in case the norms expressed by the latter diverge from the interpretations favored by central authorities).'18

Taking a step back, Schmitt’s justification for sovereign dictatorship was a critical response to what he perceived to be the fatal weakness of the ‘rule of law state’ (Rechstaat) embodied by the Weimar Republic. The inherent inability of the liberal Rechstaat to make a decisive friend/ enemy distinction had provided the conditions for factional and civil strife to flourish, to the point where the existence of the unitary State was threatened. The decisive intervention by a sovereign dictator, suspending the liberal Constitution, was justified to guarantee the State’s unity (read, survival) based on making the friend/enemy distinction, since the State’s existence was a necessary precondition for the functioning of the Constitution. In the events that happened, similar justification was used by the Nazi regime to continually suspend the Weimer constitution up until the end of World War Two.

Mitchell spells out the implications of Schmitt’s approach for the rule of law:

'… Schmitt’s own approach to the state of exception was oriented towards the displacement of authority from the judiciary and legislature to the Executive during times of emergency, … The notion that the constitutional order of the State is not in itself absolute, but rather is premised upon a certain factual state of affairs, would mean that the authority of legislators (and judges) within that constitutional order is itself contingent and relative; it may be displaced by Executive authority where needed in order to end crises and restore normality.'19

The keynote speech at the Constitution Day Seminar held on 4 December 2020 delivered by Chen Duanhong to the high-level government officials in attendance, including the Chief Executive, was titled ‘The Constitution and National Security’. Mitchell summarises:

'Chen argues that Hong Kong lawmakers, judges, or civil servants may be justifiably disqualified from their positions for disrespecting or violating their oaths to the PRC constitutional order… Any particular procedural rights that this individual might otherwise possess can be suspended for the purposes of enforcing the community-defining oath… Chen connected the issue of oaths and loyalty of government actors to [Schmitt’s] ‘concept of the political’, proclaiming that ‘the Friend/Enemy distinction is the true essence of loyalty to the State and to the Constitution’.'20

'As a barrister, I would never have imagined that I would have to address the court in the docks. On March 2 five years ago, I was sworn in as a legislative councillor, fighting for Hongkongers, but five years later, I am fighting for my own freedom.'

Returning to events on the ground, in early 2021 the Chairman of the HKBA, Paul Harris SC, became the subject of personal attack by the China Liaison Office in Hong Kong for questioning the gaoling of peaceful demonstrators and observing that public assembly and protest are protected under Article 28 of the Basic Law. The allegations against Harris by the Liaison Office, which could fairly be described as rabid, included that he:

'… repeatedly ranted to amend the Hong Kong national security law, challenge the authority of the standing committee of the National People’s Congress, and oppose the rule of law and constitutional order in Hong Kong.'

The Liaison Office then went a step further in cautioning the HKBA not to, 'walk farther down the road of politicisation. Otherwise, it will only step into an abyss it cannot get out of'. Hong Kong’s Chief Executive appeared to support that stance in making these comments:

'For the time being I do not see the case for any government intervention into the affairs of the Hong Kong Bar Association, but, of course, if there are instances or complaints about the bar not acting in accordance with the Hong Kong law, then of course the government would be called into action.'21

Responding to that partly veiled threat, the HKBA issued a press release emphasising that it is a professional body not a political organisation, defending its integrity and that of its Chairman, affirming its commitment to, 'the maintenance of the Rule of Law, the Basic Law, the independence of the Judiciary and the due administration of justice', and asserting, 'The HKBA, and its Chairman, are inviolable supporters of the fundamental policy of 'One Country, Two Systems' enshrined in the Basic Law.'22

In an interview with the pro-Beijing newspaper Sing Tao Daily23, Harris re-iterated concerns about aspects of the NSL that are inconsistent with the rule of law, such as excluding certain security officials from Hong Kong’s legal jurisdiction. He later corrected the published article misquoting him as saying that the NSL was ‘legal’ rather than saying that a form of national security legislation is ‘legitimate’.24

The events described above serve to highlight the way that the rule of law has become contested ground in Hong Kong, between liberal and authoritarian conceptions of its normative content. While the mainland Chinese legal system is often referred to as a system of ‘rule by law’ in contradistinction to the ‘rule of law’, a more sophisticated analysis is required to be able to effectively engage with the challenges posed by the NSL and other central government interventions which threaten the rule of law in Hong Kong. To limit the focus of attention to inconsistencies between provisions of the NSL and the Basic Law is akin to the chained slaves in Plato’s cave staring at the shadow-play upon the wall and believing it real. The true source of the threat to the rule of law in Hong Kong and that which illuminates the Plan, is the sovereign dictatorship of the Chinese Community Party and the influence of ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ on the constitutional order.

ENDNOTES

1 This title borrows from David Fraser, ‘The Fragility of Law: Anti-Jewish Decrees, Constitutional Patriotism and Collaboration in Belgium 1940–1944’ (2003) 14 Law and Critique 253.

2 See the discussion in Bar News [2019] (Summer), ‘A Message from the Free State of Prussia to Hong Kong’, pp. 30-32.

3 ‘Statement of the HKBA on the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’, 01.07.2020.

4 ‘No separation of powers in Hong Kong says Chief Exec. Carrie Lam, despite previous comments from top judges’, Hong Kong Free Press, 1.09.2020.

5 ‘Australian James Spiegelman resigns as judge of Hong Kong appeals court over new national security law’, ABC News online, 18.09.2020.

6 Statement of the Hong Kong Bar Association, 02.09.2020.

7 Above, n. ii.

8 Adopted by the Central Committee on 10 January 2021.

9 ‘Xi Jinping Thought on the Rule of Law New Substance in the Conflict of Systems with China’, SWP Comment, No. 28 April 2021, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, p. 2.

10 Above.

11 Above, n. ix, p.1.

12 Above, p. 6.

13 Above.

14 Assistant Professor, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Faculty of Law.

15 Ryan Mitchell, ‘Theories of Sovereignty in the Origins and Implementation of Hong Kong’s National Security Law’ (June 11, 2021), p. 25. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3863353. .

16 Reuters, ‘Reaction to Hong Kong arresting 53 in pro-democracy raids’, 6 January 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN29B06B.

17 See Ryan Mitchell, ‘Chinese Receptions of Carl Schmitt Since 1929,’ 8 Journal of Law and International Affairs 1 (2020).

18 Above, p. 251.

19 Above, n. xvi, pp. 25-26 .

20 Above, pp. 23-24 .

21 ‘Beijing calls Hong Kong bar association chief an ‘anti-China politician’, The Guardian, 27.04.2021.

22 Statement of the Hong Kong Bar Association, 03.02.2021.

23 Sing Tao Daily, 29.04.2021.

24 ‘Not What I said’: Hong Kong Bar Association Chief Clarifies security law comments’, Hong Kong Free Press, 29.04.2021.