Burigon and His Son

See footnote for acknowledgements.1

This article was written on the unceded lands of the Awabakal people.

It

includes the names, images and stories of First Nations people who are now

deceased.

One of three reforms set out in the Uluru Statement is the establishment of a Makarrata Commission – a ‘truth-telling’ inquiry into past injustices experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. A process that would 'allow all Australians to understand our history and assist in moving towards genuine reconciliation'.2

In some ways, this may seem a difficult and almost unnecessary task for those of us who are well-versed in, and overwhelmed by, the personal stories of trauma coming from our First Nations clients, the unchanging statistics of incarceration of First Australians and of their inter-generational disadvantage, and the endless reports from the various royal commissions and government inquiries. But in the absence of a Makarrata Commission, those of us who work in the criminal law can still do more to understand our history. We ought to seek out and retell the stories of those First Nations peoples who were the first to come into contact with the criminal justice system. An effective way to do this is to retell the personal histories of local First Nations peoples, those who lived in our regions and came to our courts as witnesses, victims, accused persons and offenders in the early days of white settlement.

The story of Burigon and his son,3 is one such personal history. Burigon’s death resulted in the first superior court record of a European being tried, convicted and executed for the murder of a First Australian. More importantly, their history provides a much deeper insight into the beginnings of dispossession and cultural disconnection in the Newcastle region. This is their story.

_Mclaughlin.jpeg)

In the early 1800s the white settlement known as Coal River, now Newcastle, was a cluster of tents and shacks – a mix of bush, beach, super-max prison and coal mine. It was established on the unceded lands of the Awabakal people, and as the colonialists explored north, south and west of the coastal settlement, they moved slowly on to the lands that belonged to the Worimi, Darkinung and Wonnarua people. It is a region that, like many other parts of NSW, is marked with the scars of those intrusions.4

An unlikely friendship

In 1816, Captain James Wallis, a devout Scotsman, skilled artist and acolyte of Governor Macquarie, was appointed Commandant of Coal River. His plan was to civilise the settlement – at least in an aesthetic sense. As Macquarie had done in Sydney, James Wallis immediately commenced work constructing various civic buildings, including, but most importantly to Wallis, a church built high on the hill looking over the harbour and the beaches.5

The leader of the local First Nations community at this time was an impressive man – Burigon. Unusually he was the subject of several portraits by colonial artists (including James Wallis) so it is possible now, 200 years later, to get a real sense of the man. According to those artworks he was as described: athletic, charismatic, intelligent.6

While the only records of the relationship between Burigon and James Wallis come from the latter's writings, they nonetheless depict a connection between the two men that was not only politically cooperative but also deeply affectionate. This is notable not least because James Wallis played a significant role in the Macquarie-directed massacre on the lands of the Dharawal people in early 1816 (known commonly as the Appin Massacre).

James Wallis relied on Burigon (whom he called ‘Jack’) and his tribe to track and recapture escaping convicts, a constant issue for Coal River. In return, Burigon would receive supplies and camp was set up in the grounds of the church.

Outside of their roles as leaders, the two men spent considerable time together. Burigon being able to speak some English, would tell James Wallis about his life (disputes he had with his brother, his joy at finding a new bride) and together the two men would go bush, swimming and fishing, hunting kangaroos and birds. Years later, James Wallis wrote that when he reflected on his time with Burigon at Coal River he did so 'with more kindly feelings than I do many of my own colour, kindred, nation…'.7

Two months later and James Wallis’ time as Commandant of Coal River had come to an end. He and Burigon met one last time just a few days before his departure. The picture James Wallis depicts of that last meeting is achingly poignant:

'I saw [Burigon] standing up with his only son by his side. I presumed by his countenance he had some momentous thought on his mind – he seemed agitated and … placing his hand on his son's head said with smothered feelings… I give it your permission to send [him] to school at Parramatta… and [have him] come back … to make for me a boat to fish in..'.8

To James Wallis, this gesture – the giving away of his eldest son – was 'proof of [Burigon’s] confidence in British humanity'.9 It was indeed a momentous gesture, one that Burigon clearly felt compelled to make and one suspects that the visit by Macquarie to Coal River two months earlier was a factor in either Burigon’s decision or James Wallis’ encouragement of it. It is important to recognise, however, that Burigon would not have had any real understanding of the reality of his commitment.

The school Burigon was referring to was the Native Institution. It was established in Parramatta by Macquarie in 1814 with the express aim of ‘educating’ First Nations children into the ways of the new colony by removing them from their tribes and training them into positions of gender-based servitude. At the time, this was considered progressive social policy.

Browne, Richard 1820, Burgon, watercolour and bodycolour 30.5 x 33 cm, Newcastle Art Gallery Collection

Life at the Native Institution was nonetheless predictably brutal. The children sought to escape so they were locked in at night. Parents and kin were forbidden to visit, permitted to see their children one day each a year at Macquarie’s ‘Annual Conference’ at Parramatta where:

'Children of the Native Institution will be shewn on this Occasion to their Friends; and it is hoped that their clean healthful Appearance, and contented happy Conditions, receiving Education, and acquiring Habits of Civilization and Industry, will induce the Natives to place more of their Children in a Situation so highly beneficial to them and the rising Generation.'10

Simply, the Native Institution was the very first in a long line of government policies focussed on severing the bond between the First Nations child and his or her family in the name of education, civilisation, assimilation or protection.

James Wallis accepted Burigon’s ‘offer’ and records from the Native Institution confirm that a ten year old boy from Newcastle entered the school in October 1818. The boy’s name is recorded as Wallis.

The death of Burigon – R v Kirby and Thomspon [1820] NSWKR 11

Despite Burigon’s hope that his son would return to him complete with a boat for them to fish in, they did not meet again.

Burigon died on 7 November 1820 from a stab wound sustained during a violent melee that occurred as he and a group of his tribe returned two escaped convicts they had tracked and recaptured back to their camp at the church. No one else was injured. Burigon was provided with medical treatment but died ten days later.

The response by Commandant Morisset to Burigon’s death was unusually swift and effective. This could have been the result of Morisset’s own professionalism, but one suspects a combination of two political factors also had an impact on his conduct of the matter. Firstly, Burigon was a respected and well-liked local leader, critical to the efficacy of a productive colonial outpost. Ensuring a swift and effective prosecution would have assisted Morisset’s cause as Commandant. Secondly, the workings of the entire colony, including the convict system, was at that time subject to a review by barrister and former Chief Justice of Trinidad John Bigge. Morrisset had given evidence to Bigge earlier that same year over two days and may have realised that Bigge’s final report was likely to include criticism of Macquarie’s lenient treatment of the convicts.11

Regardless as to motivation, Morisset’s role as both prosecutor and investigator was completed with genuine forensic objectivity and candour. Within ten days of Burigon’s death he had taken depositions from the four soldiers at the church camp who were on their way to collect the prisoners when the violence erupted, two local First Australian men who were part of Burigon’s group, and the surgeon who treated Burigon over the subsequent days.

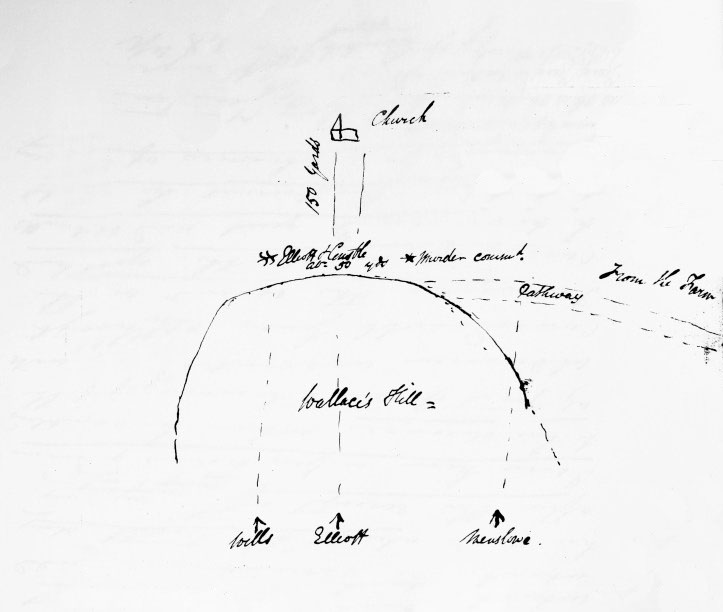

Importantly, Morisset also prepared an aerial map of the crime scene, identifying the location of the crime relative to each of the four soldiers. He likely did this because the depositions he had taken clearly revealed that the evidence of the soldiers was insufficient to found a conviction. Although one deposed to hearing what could have been considered an admission by the accused convict Kirby (an expression of regret made at the time of his arrest that 'he had not cut the bugger’s head off'), that was the high point of their accounts. As his map revealed, each of the soldiers were at least 50 yards from the scene of the attack, not one saw the fatal blow struck and each gave conflicting accounts as to who struck first.

Morisset recognised that the accounts of the two First Australian men were critical to the prosecution as they had seen how the fatal blow was struck. He took detailed statements from them, a challenge ordinarily, but fortuitously, one of those witnesses was a man named McGill, who was in fact the Awabakal leader Biraban: an exceptional linguist who not only spoke fluent English but was to become a renowned translator. His is a story for another time.

Morisset sent the depositions to Judge Advocate Wylde, making clear the importance of the Aboriginal witnesses to the case, writing: 'I shall do my best endeavours to forward Natives who witnesses the [murder] … Not one of the Military either saw or heard anything of the affair, they were some distance in the rear at the time it took place.'12

The only record of the trial comes from the Sydney Gazette.13 No mention is made of the evidence of the Aboriginal witnesses and they were not summonsed. It appears the only evidence came from three of the four soldiers and the surgeon. It was enough for Wylde, however, and the convict Kirby was convicted of Burigon’s wilful murder and later executed. The co-offender Thompson was acquitted.

Morisset recognised that the accounts of the two First Australian men were critical to the prosecution as they had seen how the fatal blow was struck

Burigon’s son

And what of Wallis, Burigon’s only son? He appears to have maintained a constant presence at the various institutions in Sydney for orphaned children, native and otherwise. He entered the Parramatta Native Institution as a ten year old boy in 1818, the Blacktown Native Institution at 17 and the Male Orphan Institution in Liverpool around January 1827 as a 19 year old man. It is possible that, given his age and likely grasp of English, he would have eventually been ‘apprenticed’ out to a local farmer or landowner at some point.

The last remaining record comes from the Court of Quarter Sessions from Maitland.14 On 14 April 1834 an Aboriginal man named Wallis was charged with breaking into the home of a local landowner and stealing flour and clothing in the company of nearly a dozen other Aboriginal men. One of the witnesses purported to identify Wallis as the offender having known him previously although the circumstances of the point of recognition are unclear.

Sketch map showing the site of Burigon’s Murder in 1820 drawn by Commandant Morisset (SRNSW: SZ 792 COD452B Court of Criminal Jurisdiction Case Papers Nov/Dec 1820 Part II pp. 496-519 Map page 507. (Courtesy of State Records New South Wales)

The Court records that the accused Wallis 'denies being there and states that [he] was at Lake Macquarie at the time.' The name Wallis and the accused’s ability to communicate his defence in English are indications this was likely to have been Burigon’s son. The reference to Lake Macquarie is also consistent. It is likely a reference to the Lake Macquarie Mission run by Lancelot Threkkeld – a place which would have been a relative sanctuary for a young Aboriginal man, fluent in English and disconnected from his culture after many years separated from his people. Wallis was committed to Greater Sessions. The outcome of those proceedings is unknown.

ENDNOTES

1 Written by E McLaughlin, Public Defenders Chambers Newcastle, with assistance from historian Dr Mark Dunn.

2 Uluru Statement from the Heart.

3 The name Burigon as spelt here is just one of many iterations found throughout historical records. Burregon, Burgon, Burgun, Burragang are also common.

4 For a map of those atrocities, see https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/map.php

5 This church was slowly replaced by the current Christ Church Cathedral in the late 19th and early 20th Century.

6 See The Wallis Album, State Library of NSW; Richard Browne, Burgun 1820, watercolour and bodycolour, Newcastle Art Gallery; Richard Browne, Long Jack [also known as Burgon or Burigon] King of Newcastle New S Wales … c 1819, watercolour and bodycolour, Mitchell Library State Library of NSW.

7 From James Wallis, Memoir, c. 1835, in Album of Manuscripts and Artworks, PXD 1008, vol. 1, f. 11. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW

8 Note 7.

9 Note 7.

10 Government Notice from the Secretary’s Office, Sydney, printed in the Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser, Saturday 19 December 1818.

11 See The Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the state of the Colony of NSW, ordered by the House of Commons to be printed, 19 June 1822, London 1822, at 117, which shows that a particular focus of Bigge’s questioning of Morisset was the issue of escaping prisoners with positive mention made of the assistance of local Aboriginal people in tracking and capturing the fugitives.

12 Criminal Jurisdiction Case Papers Nov/Dec 1820 Part 11 pp 496-519, SANSW.

13 R v Kirby and Thomson [1820] NSWKR 11, Court of Criminal Jurisdiction, Wylde JA, 14 December (or 22 November) 1820, from the Sydney Gazette, 16 December 1820.

14 SANSW: NRS 845, [4/8410] ‘Quarter Sessions - Maitland Papers 1834-35’. (Reel 2407).