A Short History of Criminal Law - Francis Forbes Society Australian Legal History Tutorials

Wednesday 18 October 20171

Introduction

Writing in 1981, Milsom opens his chapter on the history of criminal law with this: 'The miserable history of crime in England can be shortly told. Nothing worth-while was created.'2 It was a rather uninspiring way to begin my preparation for this address. My aim this evening is however to persuade you all that the history of our criminal law – including its English origins, Indigenous influences, and Australian innovations – is neither miserable nor short. I’m confident you will at least believe it not to be short; I do have an hour to speak…

Firstly, however, I should perhaps give some explanation as to why I chose to deliver a tutorial on this topic, as no doubt some of you are wondering from where, after 35 years at the commercial bar, my sudden interest in criminal law has sprung. In fact, one of my first cases at the bar was a criminal matter an unlosable case which, I lost – rendering my early experiences with the criminal law quite miserable and perhaps part of the reason I steered clear of it in the years that followed.

Nevertheless, at least half of my current caseload is criminal, and my current job also involves communicating with government on law reform, crime often being the top of each new government’s agenda. No doubt most of us here believe in the importance of looking back to understand the way forward, and so, I agreed to give this address in part to allow me to delve back into the history of criminal law for myself. The natural starting point, lay of course in the reign of King Aethelbert, Kent, 600 A.D. It is here that we find the earliest preserved record of Anglo-Saxon criminal laws, and where I shall begin tonight’s tutorial.

Anglo-Saxon era

To describe these laws as criminal in nature is perhaps misleading – as Maine states: 'the penal law of ancient communities is not the law of crimes, it is the law of wrongs, or to use the English technical word, of Torts'.3 Three sets of these laws, known as 'dooms' have been preserved, the first being issued by King Aethelbert around 601 A.D. They were tort-like in their essential concern with the compensation of victims as opposed to the punishment of offenders.4 However, the purpose of the dooms was to countenance vengeance by blood-feud that had prevailed since the departure of the Romans5 and was beginning to be seen as an interference with public peace. We can, therefore, see glimpses here of the shift from criminal law as in the hands of individuals wronged to a recognition of the need for state involvement.6 The solution presented by these dooms was agreed sums in compensation for injury – basically a civil indemnity, known as a bot – payable regardless of intent, or anything personal to the offender.7

Where the parties couldn’t agree on the amount, the king set a tariff according to the social status of the injured party, and the level of injury. A damaged bone, for example, was worth four shillings, and an eye worth fifty.8 An additional fine, known as wite, was payable to the King, who used the law to enhance his own wealth in addition to taxation.9 However, for the worst offences, which were considered botleas – inexpiable – the consequence was mutilation or death.10

In relation to offences against God and the Church, the dooms provided for fines payable to the Church for theft of its property, compensated twelve-fold that of the ordinary crime.11 The third dooms, issued by King Wihtraed in 695, provided penalties for heathen practices, the neglect of fasts and holy days.12 It was also by this doom that the Church was declared immune from taxation.13

Early courts and trial by ordeal

The Anglo-Saxon courts were, by 900 A.D., essentially local popular assemblies, somewhat democratic in nature, which met in the open air every four weeks.13 The king’s 'reeve', a senior official with local responsibilities of the Crown, presided on the courts, but judgments were given by peasants. Each shire also had a county court presided over by a nobleman and a bishop, with jurisdiction over murder, theft, affray and wounding.14

With the introduction of this system of 'trial' came the need for a means for determining truth and guilt. An accused had to seek a verdict from God, either through 'compurgation' or ordeal. Compurgation required the accused to swear an oath that they were guiltless, and if they could produce sufficient 'oath-helpers' who would vouch for their character on oath, that was evidence of innocence.15 If unable to find oath-helpers, the trial would be by ordeal which was administered by the Church.

The most common methods required the accused to handle hot iron or plunge their hand into hot water unscathed.16 A third form, the ordeal of water is surrounded by some confusion – sinking was the sign of innocence and floating the sign of guilt – but unless hauled out in time, those who sank wouldn’t have the opportunity to enjoy their acquittal, alive at least.17 Stephen suggests that it may have been an honourable form of suicide for some.18

Trial by ordeal continued until 1215 when a decree of the Fourth Lateran Council prohibiting clerical participation in ordeals put an almost instantaneous halt to the practice. The ending of this as a system of trial led to a vacuum that was eventually filled in Europe by the introduction of the judicial inquisition, and in England by the rise of the jury.19

The king’s peace

Before we move beyond the Norman Conquest, it would be remiss of me not to mention the laws of King Cnut in the eleventh century, as he was first to compile a list of what were later understood to be Pleas of the Crown.20 These laws are viewed as the first step in the development of the concept of the King’s peace – being the notion that crimes are committed against the Crown, and that the Crown has the authority and right to keep the peace.21

King Cnut declared that he had a special interest in certain cases, and brought them directly before himself or his sheriffs. The types of cases included a violation of the King’s personal peace, attacks on people’s houses, ambush and the neglect of military service.22 The result, and perhaps purpose, was to create a profitable source of crown revenue.23

At the time of the conquest, the King’s peace was limited temporally and spatially – it existed, for example, for a week after coronation, at Christmas and Easter. Spatially, for example, it was concerned with things such as the protection of great roads – the laws of William the Conqueror provided: 'of the four roads, to wit Watling Street, Erming Street, Fosse, Hykenild, whoso on any of these roads kills or assaults a man travelling through the country, the same breaketh the king’s peace'.24 Thus assaulting a person on these roads became a wrong against the Crown, not merely the individual. Pollock traces the term the 'the king’s highway' back to this peculiar legal sanctity given to particular roads.25

After the conquest the king’s peace came to be proclaimed in general terms at his accession. However, it was hamstrung by peculiarity – temporally still confined to the reign of the particular King, not the 'Crown' generally as an authority having continuous succession. After the death of one king and before the successor was crowned, the king’s peace would cease and chaos reigned. A practicality brought about the modern notion of the king’s peace – at the time of Henry the III’s death, his son was away in Palestine, so in his absence, peace was proclaimed in the new King’s name forthwith.26

Pleas of the Crown

In the first few decades after the conquest, acts regarded as criminally culpable still largely remained in private hands for redress. This changed as the life of the community became more settled, and the Crown turned its attention from consolidating power to the suppression of disorder.

Following the anarchy that had ensued during the misrule of King Stephen, Henry the II, the 'lawyer king', began transforming the criminal law of England. Minor crimes were still dealt with in the hundred and county courts, but Pleas of the Crown committed against 'the peace of … the King, his Crown and dignity' were prosecuted by the King, and fines payable to the King replaced the compensation system.27

Plucknett attributes this change to two underlying forces: the first, a familiar theme – the desire to increase Crown revenue. Secondly, however, was the fact that the procedure for a victim or their kin to achieve criminal justice had become too difficult – the task, if it were to be completed, necessarily fell to the Crown.28

Around the same time, the jury trial and the concept of an indictment were beginning to form. The Assizes of Clarendon and Northampton, of 1166 and 1176, provided that accused persons were to be presented to the king’s justices by a grand jury made up of representatives from neighbourhoods where the crimes were committed, as a public indictment. If the accused person was caught, they were then sent to the ordeal.29

The modern form of indictment is rooted in this practice. It developed to the point that by the 1360s, a draft written form of accusation – the bill of indictment – was prepared in advance of the session of the grand jury. The grand jury would then consider the bill. The effect of the jurors swearing the bill was a billa vera – true bill – was a finding that there was a case to answer, and formed a written accusation upon oath that initiated proceedings between the king and the accused.30

The end of the ordeal in 1215 did not lead immediately to the creation of the trial jury – first, royal judges were simply ordered to banish those presented to them by grand juries,31 and those accused of serious crimes were to be remanded in prison, seemingly indefinitely.32 English judges instead started to make use of the locals already in court as representatives from the neighbourhood who had formed part of the grand jury, who were put on oath to decide the question of guilt.33 Given the accused had generally been indicted by these very representatives; he or she was 'rather at the mercy of their prejudice'.34 Nevertheless, trial by jury rapidly became regularised and by 1351 the jurors were required to be different from the members of the grand jury who had presented the indictment.35

The sequestration of the jury also developed, enforced rigidly to the extent that the jurors were like prisoners. When considering a verdict they were to be confined 'without meat, drink fire or candle' until they were agreed on a verdict.36 The rules were strictly enforced – in 1587, four jurors were fined for merely being in possession of raisins and plums.37 If they could not agree, they were to be carried around the circuit in a cart until they did. I’m sure some of our common law judges feel some nostalgia for the old days when juries fail to return verdicts following months-long trials.

The discomforts were also intended to encourage unanimity in the verdict, although in its absence the result was left to the judge. In what Pollock and Maitland describe as a judicial scheme to avoid the trouble and moral responsibility of 'deciding [guilt or innocence] simply on their own opinion',38 we find in 1367 a decision of the Court holding a majority verdict to be void.39

It is interesting to pause here and consider the contrast between the popular culture view of one’s 'right' to a trial by jury, as compared to its historical foundations. The jury trial at its inception was hardly viewed as the palladium of English liberty, but rather an innovation forced upon the law and its subjects by the end of the ordeal.40 In fact, Plucknett opines that the Crown originally felt it was unreasonable to compel someone to submit to trial by jury.41 Thus it became customary to ask the prisoner how they wished to be tried – the correct answer being 'by God and the country'.42 However, unless they could be persuaded to give that answer, they had to be kept in prison for want of any other solution.43

In 1275 Parliament moved to impose jury trial by force, providing by statute that 'notorious felons who are openly of evil fame and who refuse to put themselves upon inquests of felony … shall be remanded to a hard and strong prison as befits those who refuse to abide by the common law of the land’.44 By some misunderstanding, the words prison forte et dure were read as peine forte et dure, and by the 1300s the procedure had morphed into a form of torture of placing the accused between two boards and piling weights upon them until they accepted trial by jury or expired.45 Those with no hope of acquittal, however, would somewhat cleverly choose this fate in order to die unconvicted and thereby save their dependants from forfeiture of their property.46

Despite the continued reverence in popular culture of the rights-based understanding of a jury trial, this early history of the jury trial continues to dominate its modern legal conception. Just last year in Alqudsi v The Queen47 the concept of peine forte et dure was discussed by the High Court in considering the question of whether an accused person in federal jurisdiction could be tried on an indictment by a judge-alone, or whether that proposition was inconsistent with s 80 of the Constitution.48 The question had been decided adversely to the applicant in 1986 in Brown v The Queen,49 and the majority chose not to distinguish or reconsider that case. In Brown, Brennan J held that the concept of 'waiving' the 'right' to a jury trial, accepted doctrine in the United States,50 was antithetical to the history of trial by jury at common law, as the law of England had for so long compelled accused persons to submit themselves to trial by jury.51 Similarly in Alqudsi the plurality conceptualised s 80 as not being primarily concerned with the protection of individual liberty, but rather as an institution of importance to the administration of criminal justice more generally, and pointed to the benefit to the community of having guilt determined by a representative, or quasi-democratic body, of ordinary citizens. 52

The appeal of felony

Stepping back to where we were, being the early development of the jury trial and the indictment, it is important to note the other manner in which criminal proceedings could be commenced – through 'the appeal of felony'. This was an oral accusation of crime made by either the victim or by 'approvers' – an accomplice who received immunity in return for undertaking to prosecute their fellow wrong-doers. It has its origins in the early private process for the punishment of crimes where compensation was paid to the injured party – although compensation was no longer available, the private process remained.53 Initially these proceedings involved the complainant raising the 'hue and cry' and then making an oral complaint in the county court before the justices in eyre. It later morphed into an appeal at the assizes or at Westminster.54

The essential purpose of these proceedings was punishment and forfeiture – a way for victims to recover stolen goods or seek revenge.55 For an approver, a failure to successfully prosecute the appeal would result in hanging – in one case in 1327, the approver was hanged when the appellee absconded to Flanders.56 By the 1500s, victims’ appeals were increasingly brought only as a way of actually bringing the defendants to court, and the prosecution was then taken over in the king’s name. Judicial views were varied about the appeal process – in the case of Stout v Cowper in 1699 two judges labelled it a 'revengeful, odious prosecution' deserving no encouragement, while Chief Justice Holt described it as 'a noble prosecution, and a true badge of English liberties'.57 Nevertheless the process died a natural death,58 and was formally abolished in 1819.59

Emergence of the prosecutor

As the criminal law came to be enforced by the state rather than individuals, the slow move towards the concept of public prosecutions began. The 14th century saw justices of the peace emerge as 'public prosecutors' of sorts. These JPs were members of the community – selected from knights and wealthy landowners,60 appointed by the king to serve as keepers of the peace, with the power to inquire into and present an accused before a grand jury. Originally they supplemented the existing methods of prosecution, stepping in only when private individuals did not pursue the matter. Gradually the role expanded to the point that justices of the peace had responsibility for investigating the commission of serious crimes once complaint had been made. Distinct from this procedure, however, was the right of the Crown to place an accused on trial by an ex officio indictment – this was the manner in which most cases heard by the notorious Star Chamber were presented, an institution that was thankfully abolished in 1641.61

The industrial revolution saw an increase in urban population and crime, which in the 18th century was countered by organised groups of private agents known as 'thief takers', who would receive monetary rewards from the government for successful prosecutions – who could have guessed, the result was widespread false prosecution and perjury.62 In 1829, the London Metropolitan Police was established, which took over the responsibility of prosecution.63 However, the private nature of the prosecution remained – when initiating a prosecution the police officer was acting 'as a private citizen interested in the maintenance of law and order'.64 The right to privately prosecute a criminal offence is still recognised in all Australian jurisdictions.65 In New South Wales this operates with the qualification that the DPP may take over the prosecution and discontinue it, and leave of the court is required.66

The development of trial procedure

As concerns trial procedure, the accused was originally permitted to plead their case orally – essentially through making an unsworn statement in response to the victim’s sworn evidence. However, they were allowed no help from counsel – a rule defended on the ground that the evidence to convict should be so clear it could not be contradicted. This lofty goal in practice was hardly realised – the average length of a trial was mere minutes and reports of the Old Bailey trials in the nineteenth century were that prisoners could hardly tell what had transpired in Court – frequently not even knowing whether they had in fact been tried.67

From the 1730s, prisoners were allowed counsel and it was made a legal right in 1836. Increasingly, it became possible for an accused to mount a defence without giving a statement, which changed the ideology of a criminal trial from one requiring a defendant to tell their story to one requiring the prosecutor to make good theirs.68 It was not until 1898 that accused persons were in fact allowed to give evidence on oath – until that time an accused person was not considered a competent witness because of their own interest in the case.69 This right to make an unsworn 'dock' statement was reflected in legislation in New South Wales in 1883,70 which provided for the statement to be made at the close of the prosecution case, and that the accused was not to be cross-examined. In NSW, the right was not abolished until 1994.71

The substantive criminal law: corporate crime

Up to this point we have focussed mainly on matters of procedure, and little on the substantive criminal law. To return to quoting Milsom: 'there is either too much to say or too little'.72 For Milsom, there is too little because in terms of the early criminal law, we have only records reciting the indictment, facts and verdict, concealing 'matters which would to us be matters of law'.73 For myself, and particularly as we approach the turn of the century, there is simply too much to say, and for that reason I hope you will indulge me briefly as I focus on the development in the 19th century of corporate offences – something I can at least pretend to know something about.

The rapidly developing economy of the 1800s presented an array of new opportunities for dubious dealings and the legal system at that point had few tools to deal with these new forms of behaviour. Obtaining 'by any false Pretence … any Chattel, Money or valuable Security, with Intent to defraud' had been a crime since 1757.74 In practice, however, this law was ill-fitted, and rarely employed, to deal with joint-stock fraud. In the 1840s, however, the exposure of the enormous Independent West Middlesex Assurance Company as a fraud sparked a change in government attitude about joint-stock morality, and legislative measures to bring companies within both the civil and criminal law.75

And so we find, in the Joint Stock Companies Act 1844, not only a number of measures to promote good corporate governance, but the explicit extension of the criminal law to company directors. It stipulated that if any director or other officer of a joint-stock company were to wrongfully do or omit to do any act, with intent to defraud the company or any shareholders, or falsify the records of the company, they would be deemed guilty of a misdemeanour.76

However, the statute failed to achieve the lofty goals of its supporters. The prevailing judicial attitude was that unless the company was entirely a bubble scheme without any real existence, these were problems for the civil law.77 Even when shareholders turned to the civil law for redress, moral judgments condemning the actions of speculators tended to prevail.

The case of George Hudson, the 'Railway King', exemplifies one such moral response. Hudson was the chairperson of four of the biggest companies of the railway boom in the 1840s, generating massive profits from railway schemes. Rumours of dubious practices led to an evaporation of shareholder confidence. Inquiries revealed that he had falsified balance sheets to justify unwarranted dividends. To be fair, his misdeeds must be viewed in their context, where there were differences of opinion in accounting circles about how to apportion charges between capital and revenue. However, he had also misappropriated company funds and committed related breaches of trust. Despite the press describing his actions as 'enormous frauds', there remained hesitancy to invoke criminal penalties. The sticking point was the perceived complicity of his shareholders in creating the bubble – the Times wrote that 'the full measure of contempt will be reserved, not for the idol but the worshippers', who should have been satisfied with 3% but greedily demanded 9%.78

Public opinion shifted, however, with the collapse of a number of banks in the 1850s, which provided impetus for the introduction of a bill by Sir Richard Bethel in 1857 that took into account various forms of breach of trust and explicitly addressed joint-stock company frauds. Significantly, it specified punishments (unlike the 1844 Act), including penal servitude and imprisonment with or without hard labour – showing us that these offences were now being taken seriously.79 The decade also saw, in 1858, the first big white-collar prosecution of the directors of the London and Eastern Banking Corporation, which had loaned practically all of its paid-up capital to a director, who had lost it all.80 The crux of the prosecution case was simple: the bank was insolvent, the defendants knew it, and lied about it to shareholders.81 Following a guilty verdict for all six directors and the manager, the sentencing decision emphasised the importance of general deterrence in such cases, a principle now entrenched in cases of white-collar and corporate crime. The Lord Chief Justice John Campbell rejected the defence that what management had done was a common practice, emphasising it made punishment all the more necessary: 'a laxity has been introduced into certain commercial dealings, not from any defect in the law, but from the law not being put in force'.82

Indigenous Australia and crime

It is time perhaps now to travel back a few years and into the criminal law of this country. Obviously, however, it does not begin with the arrival of English law. It is difficult to do justice to the 40, 000 years of indigenous legal history briefly, particularly so because it is dangerous to generalise about the variety of clans and customs that existed.83 It is also difficult to examine customary law from the prism of the British legal system, as the distinction we would understand between the law on one hand, and social norms on the other, did not exist.84

Nevertheless, an oft cited study by Meggitt in 1962 of the Walbiri people found that post-contact, it was possible to define offences and the punishments that followed them. The punishments included death, insanity or illness, wounding intended to draw blood and battery with a club or boomerang, oral abuse and ridicule. Ridicule was mainly directed at the offences of omission, being physical neglect of relatives, refusal to make gifts to certain relatives and refusal to educate certain relatives.85 Interestingly, Clifford, though noting the difficulty with generalisations, suggests that the First Nations peoples treated many cases as being more civil wrongs than criminal offences – that is, looked to compensation and damages rather than punishment.86

Also of importance are kinship relationships in First Nations law. Some kinds of behaviour may be made lawful or unlawful by virtue of the kinship roles involved – seemingly innocuous language, for example, might be a legitimate and excusable cause of violence when used to someone who should not be spoken to.87

When the first fleet arrived in Australia, it was accepted doctrine that English law regulated the legal relationship between colonists and First Australians. The colonists view on whether English law should regulate the relations of indigenous people with each other was less clear, and some took the view that indigenous people should be governed by their own laws.88 The matter was settled in 1836 by the Supreme Court of New South Wales, deciding that English law should apply to offences committed as between indigenous people.89 Unease continued within the judiciary – Cooper J, in South Australia remained unwilling to concede the point, and argued he required a legislative direction if such cases were to be justiciable.90

These concerns have remained, and produced numerous law reform commission reports over the years on the recognition of customary law.91 However, in the criminal sphere, legislatures seem firmly committed to the common law position, particularly in relation to sentencing. In the Northern Territory, for example, s 16AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), introduced in 2006, precludes NT courts from taking customary law or cultural practice into account when sentencing. In one case, involving sexual assault contrary to the Criminal Code (NT), it was noted that ordinarily the kinship relationship between the victim and offender would have aggravated the offending, but the court was precluded from taking such circumstances into account and did not do so.92

However, there have also been attempts to reform the legal system to tailor more closely to the needs of First Nations people. In Victoria, for example, the Koori Court was introduced in 2005, which involves Koori elders providing a magistrate with advice relating to cultural matters.93 In New South Wales a Youth Koori Court was established in Western Sydney as part of the Children’s Court in 2014.94 Circle sentencing was also introduced in New South Wales in 2002, a process involving community elders, the magistrate, the offender and in some cases the victim determining an appropriate treatment plan for rehabilitation, an appropriate sentence, and providing support to the offender in successfully rehabilitating.95

The colonial period

In relation to colonial Australia, and particularly New South Wales, the importance of the criminal law can hardly be overstated. To quote Dr Woods: 'the criminal law of England was the reason why convicts were in New South Wales, and the criminal law was central to the first few decades of the colony'.96

Originally, criminal justice was handled by the office of Deputy Judge-Advocate, filled by a military officer, commanded to both perform judicial functions and to observe and follow such orders and directions as received from a superior officer – entirely incompatible with how we now understand judicial power.97 The first decade from 1788 saw a peculiar mixture of common law and martial law. Instead of a jury of 12, there were seven military officers.98 Punishments were severe, even for seemingly innocuous crime, and hangings were common, as was the flogging of male convicts. In 1790, for example, two convicts received 500 and 2000 lashes respectively for stealing biscuits.99

Martial law was to take a dominant place from 1795, when Governor Phillip left New South Wales and Major Francis Grose became acting governor – Dr Woods reports that he saw the colony as a martial outpost, ordering that convicts were to be punished on the order of the Lieutenant Governor. Nevertheless, the criminal courts of New South Wales did develop some basic notions of trial according to evidence proved to a sufficiently high standard.100

I will pass over the Rum Rebellion years and move on to the struggle for trial by jury in the new colony. As we have seen, in the United Kingdom, the jury system was more of a necessity pushed upon the system by outside forces. In the colony, consistent campaigning on the part of emancipists led to the transition from the military jury to the trial jury of 12. Governor Macquarie began the political struggle, which would last over a decade, around 1809. He had everyday contact with emancipists, leading him to the sensible view that many criminals reformed and could become productive citizens.101 In 1819, leading emancipist citizens signed a petition calling for legislation to protect their legal rights.102 However, these efforts were stifled by a report produced in 1823 that expressed the view it would be dangerous and inexpedient to submit the life of a free person to the judgment of remitted convicts.103

A small battle was won in 1823, the year which saw the passing of the Imperial New South Wales Act and the establishment of the Supreme Court, with this society’s namesake, of course, presiding as its first Chief Justice. Its provisions reflected the view of the report – that the jury trial should be by a panel of commissioned officers under the direction of the judge.104 However, section 19 of the Act allowed for the establishment of a court below the Supreme Court, of 'general or quarter sessions', to try criminal cases not punishable by death. In England, a Quarter Sessions trial was by a jury of 12. A question of statutory construction arose – should the lower court consist of a civilian jury or not? Sir Francis Forbes’ reasoning, consistently with the now-orthodox principle of statutory interpretation, resolved the question in favour of fundamental common law rights and freedoms, which are not taken to be diminished other than by explicit language.105 Section 19 did not prohibit trial by jury at Quarter Sessions, and as such a procedure was established in England, the Chief Justice reasoned it should be adopted in the colony.106

Nevertheless, Sir Francis’ decision was not met with approval from London, and by the Australian Courts Act 1828, the jury trial was abolished in Quarter Sessions.107 However, that Act was a small win for the emancipists – by s 10, the Legislative Council was empowered to determine future policy on jury trial.108

The next step was an Act providing for some emancipated convicts to sit as jurors – but subject to a bad character test, leaving magistrates who prepared jury lists with the discretion to exercise their prejudices against former convicts at will.109 Governor Bourke campaigned with the English parliament for a change to the law, seeking the opinion of three Supreme Court judges (Forbes, Dowling and Burton) as to the competency of persons whose sentences had expired to be jurors in England. They affirmed that under English law there was no 'bad fame' test, and their opinions bolstered Bourke’s case, resulting in the Jury Trials Amending Act 1833, extending civilian jury trial as an alternative to trial by military jury. Emancipated convicts were now able to serve as jurors both in the Supreme Court and at Quarter Sessions criminal trials.110

However, the debate raged on, egged on by the Sydney Herald on behalf of the 'respectable' population who railed against the imposition of so-called 'Convict Jury Law'. Bourke was forced again to ask for opinions of the judiciary. Chief Justice Forbes and Mr Justice Dowling both agreed that the jury system was suitable, but in true judicial fashion, the third judge disagreed

Mr Justice Burton stating that those empanelled were 'frequently … very improper persons' who were unwilling to convict even on clear evidence.

The judges also differed in their opinions as to why 'respectable' people were not serving on juries – for Burton it was because it required decent people to associate with the disreputable emancipists, while for Forbes, it was 'the unwillingness of the upper classes … to be drawn so frequently from their private affairs … to attend [a] painful duty in the Courts'.111 In the end, the issue was resolved, as things often are, by revenue considerations – the British authorities were over paying for the upkeep of the military establishment required for the juries, and by 1839 it was dispensed with.112

The jury trial and First Australians

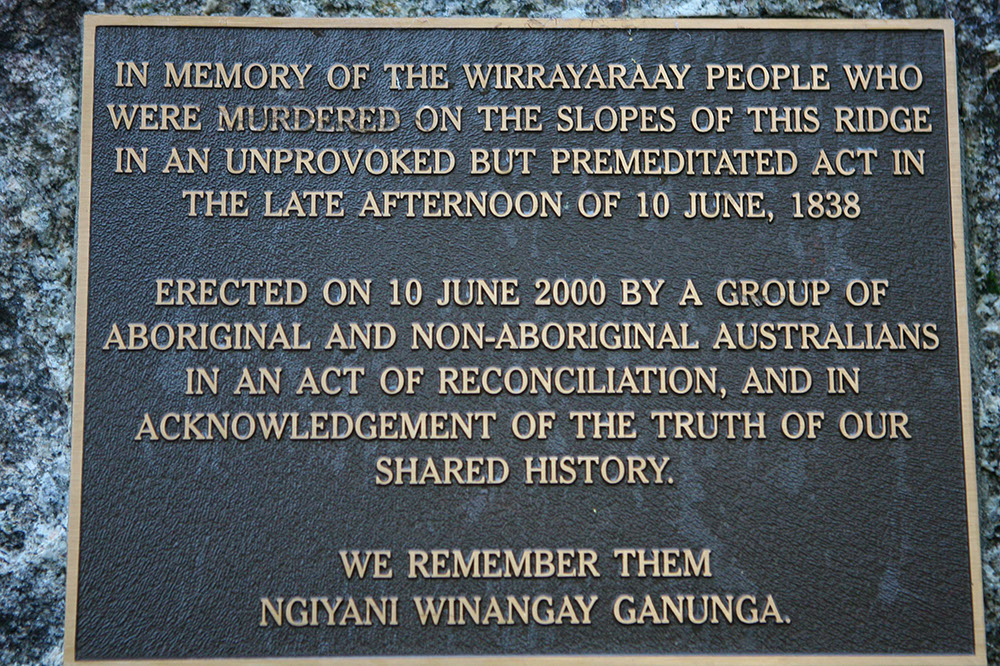

However, despite the ultimate win for the emancipists, it is important to remember that the jury trial was not quite a 'palladium of liberty' for all the inhabitants of the colony. The jury system certainly did the First Nations inhabitants of New South Wales no favours. I’m sure we are all aware of the infamous Myall Creek Massacre Case – often remembered as an example of white settlers being brought to justice for the killing of 28 First Australians. A lesser-known incident is the Snodgrass Lagoon massacre, which was never prosecuted. Woods records that the Attorney-General, John Plunkett, recognised it would be useless to charge because there was no possibility of a white jury convicting, after the public outrage at the hanging of the Myall Creek killers. In the decades that followed, a number of indiscriminate killings and massacres went by entirely unpunished, as for a long time no New South Wales jury was entrusted to fairly try the murder of First Nations people.113

The relationship of indigenous Australians with the criminal justice system is shaped by these historical interactions, and we continue to face the difficulty of mistrust in juries that lack racial diversity. First Nations people, we know, are significantly overrepresented as defendants in criminal trials – 31% of all cases that proceed to trial involve First Nations defendants. However, First Nations people constitute less than 0.5% of all jurors.114 What this means is that the 'peers' that First Australians often face rarely come from their communities, feeding into a lack of confidence in the administration of justice, which requires our continued attention.

The last 100 years: some milestones

Turning to the development of the criminal law post-federation, with the time we have left, I intend to focus on some important milestones in Australian criminal history that I hope you will find of interest. The first was the codification of the criminal law in some jurisdictions, immediately following federation.

Codification

It is important to situate the approaches of the different states to codification by reference to the context of half a century of failed codification attempts in the UK.115 Bentham was the early theoretical proponent of codification, with the aim of such clarity that both the average person and the average judge could understand it.116 While consolidation was pursued actively in the early 1800s, Lord Chief Justice Ellenborough’s defence of judicial power and the common law came to dominate the debate throughout the 1800s.117 The final effort came from Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, who drafted in 1878 a code which, in an attempt to achieve consensus, left much open to judicial interpretation including defences and liability.118 Lord Chief Justice Cockburn declared, however, that no code was better than such a half-baked one.119

In this country, Queensland was an early adopter of codification. Wright attributes the difference between those codified Australian jurisdictions and the situation in the UK as due to two historical factors. Firstly, it was a means of rationalising the overly complex mix of applicable English laws and colonial legislation. Secondly, the bar and bench were in stages of infancy relative to their UK counterparts, with both sides facing difficulties accessing the relevant statutes and scarce expensive legal texts, so codification was ideal.120

It should also be remembered that codification developed in the context of constitutional change in Australia – with Sir Samuel Griffith, author of the Queensland Code, leading the Queensland delegation to the Melbourne Constitutional Conference. This is significant when we reflect on the larger notions that it is said to represent: parliamentary supremacy over the content of the law and limiting the role of the unelected judiciary to interpretation, as well as the democratic values of prospectivity and certainty.121

Griffith’s code in many ways is founded on Stephen’s earlier draft code, with a significant difference – drawing inspiration from the Italian Code, he also set out the principles of criminal responsibility, and defences – putting it 'even closer to Bentham’s conception'.122 Griffith’s constitutional background can be seen reflected here – his criticism of the UK Bill was based on the value of parliamentary sovereignty.123 The Griffith Code came into force in Queensland in 1901.124 In Western Australia the same Code was enacted in 1902,125 Tasmania enacted its Code in 1924126 and the NT in 1983.127 The ACT became partially codified in 2002.128

In New South Wales the debate had begun in the 1870s over the Criminal Law Consolidation and Amendment Bill, an act to consolidate and amend the various statutes in which the criminal law was contained at that time. After a decade of debate, it was eventually passed. Critics of that Bill had suggested the colony should adopt a Code instead, but Sir Alfred Stephen in defending the bill stated it was desirable to wait until the Parliament of Great Britain passed Stephen’s Code into law, to have the 'advantage of the decisions of the English courts on the various provisions'. As it came to pass, the bill never passed in England, and New South Wales has never codified.129

Abolition of capital punishment

The next milestone was one commemorated earlier this year – the abolition in Australia of capital punishment, it being 50 years since the last state execution in Australia, that of Ronald Ryan at Pentridge Gaol. In this state it was abolished in 1955 for all crimes,130 and in 2010 the federal parliament legislated pursuant to the Foreign Affairs power to ensure it could not be reintroduced by the states.131 The issue remains one of significance in the Australian legal community, and in Australian politics, with the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade in 2016 reporting on Australia’s efforts for worldwide abolition – important in today’s borderless world, where Australian citizens may end up subject to this 'cruel and inhumane' penalty elsewhere in the world.132

Women and the criminal law

Perhaps better described as reform rather than a milestone, a further change we have witnessed over the last 100 years is the relationship women have with the criminal law, particularly in the field of sexual assault, a species of crime which disproportionately affects women in society. We have seen the complete reconstruction of the concept of rape from requiring the use of threat of force or violence, and provable resistance, to an offence centred on the concept of consent.133

We also saw the abolition of the marital rape exemption. New South Wales was the first Australian jurisdiction to abolish this alleged exemption by legislative amendment, in 1989.134 During the 1970s and 1980s all Australian jurisdictions also enacted 'rape shield' laws, imposing limitations upon the cross-examination of complainants and the admission of evidence relating to complainants’ prior sexual history.135

Despite positive changes, stereotypes remain common in society and within the system. A study using mock juries has shown that pre-existing attitudes about sexual assault influence judgments more than the facts of the case presented, with juries bringing with them strong expectations about how a 'real' victim should behave.136 As Mary Heath has stated, 'breaking this cycle requires that decision making … be based in the contemporary – as opposed to the historic – state of knowledge'.137 Perhaps this is one area where the continued influence of history has been unhelpful, and we need instead a clean break if reforms are to achieve their stated goals.

Victims and the criminal law

The final milestone of the 1900s I will canvass is the legislative refocus on the rights of victims. In early modern law, we saw the gradual withdrawal of the victim from the criminal justice system. These moves were seen as progress towards a more rational system of adjudication and punishment compared to the arbitrariness of private vengeance. In the post-modern era, we have seen re-acknowledgment of the victim in criminal proceedings. In 1996 a suite of statutory reforms was introduced in New South Wales addressing victims’ rights and victims’ compensation.138

The response to these reforms has not always been positive, with some concerned that concessions to victims come at the expense of the rights of defendants.139 On the other hand, others suggest that a victim who is not alienated by the criminal justice system is perhaps more inclined to cooperate with it and report crime in the first instance.140

A side effect of the historic exclusion of victims from the system has also been victims’ increasing resort to civil sanctions. For example, in 1999 a First Nations woman and her three adoptive sisters brought an action against the sons of their foster family for the trauma of sexual assaults committed against them. The payout awarded was one of the first made to children of the stolen generations – although not officially a 'stolen generation' case. Tellingly, however, the plaintiff maintained the case was really about seeing justice done – stating that it was 'the apology from the magistrate that was really pleasing'.141 While tort and crime are of course distinct areas of law, we see remnants of their historic union in this continued availability of civil remedies for most criminal acts.

Conclusion: the challenges ahead

Finally, the turn of the 21st century – an era which has seen significant changes in both substantive and procedural aspects of the criminal law. We saw the introduction of the Uniform Evidence Acts in the late 20th century, and the judicial angst their interpretation has caused – which is, thankfully, starting to settle. We have also seen the rise of preventive detention regimes to address the challenges of terrorism and violent and sexual offending. And we have the rise of cybercrime – no doubt the rapid technological development that we are experiencing will continue to test the existing boundaries of the criminal law. I do hope the day that some poor counsel attempts to explain the theft of cryptocurrency to the bench comes long after I have retired. Whatever happens, it remains important that the safeguards we have developed over the last 1500 years to ensure fairness to defendants and victims are maintained and defended, as we move into this new, and extremely difficult era, of criminal regulation.

ENDNOTES

1 I express thanks to my Judicial Clerk, Ms Naomi Wootton, for her assistance in the preparation of this address.

2 S Milsom, Historical Foundations of the Common Law (Butterworths, 2nd ed, 1981) 403.

3 A K R Kiralfy, Potter’s Historical Introduction to English Law (Sweet & Maxwell, 4th ed, 1958) 346.

4 John Hostettler, A History of Criminal Justice in England and Wales (Waterside Press, 2009) 14.

5 Ibid 15.

6 Kiralfly, above n 2, 346.

7 Hostettler, above n 3, 15.

8 F L Attenborough, The Laws of the Earliest English Kings (Cambridge University Press, 1922) 9.

9 Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, A History of The Criminal Law of England (Macmillan & Co, 1883) vol 1, 57.

10 Ibid 58.

11 Attenborough, above n 7, 4.

12 Ibid 25.

13 See ibid 121.

14 Hostettler, above n 3, 18.

15 Stephen, above n 8, vol 1, 72.

16 Ibid 73.

17 Hotsettler, above n 3, 20-21.

18 Stephen, above n 8, vol 1, 73.

19 Herbert A Johnson, History of Criminal Justice (Anderson Publishing, 1988) 47-51.

20 Kiralfy, above n 2, 350.

21 Ibid.

22 Sir Frederick Pollock, Oxford Lectures and Other Discourses (Macmillan & Co, 1890) 84-7; Kiralfy, above n 2, 350.

23 Hostettler, above n 3, 37.

24 Pollock, above n 22, 80.

25 Ibid 82.

26 Ibid 88. See also Kiralfy, above n 2, 351.

27 Hostettler, above n 3, 46-7; Theodore Plucknett, A Concise History of the Common Law (Butterworth & Co, 4th ed, 1948) 402.

28 Theodore Plucknett, Edward I and Criminal Law (Cambrdige University Press, 1960) 66.

29 Kiralfy, above n 2, 352.

30 J H Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History (Butterworths, 4th ed, 2002) 505.

31 Johnson, above n 19, 62.

32 Baker, above n 30, 507.

33 Ibid 508.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid. See Stat. 25 Edw. III, stat. v, c. 3.

36 Ibid 75.

37 Ibid.

38 Sir Frederick Pollock and Frederick William Maitland, The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I (Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed, 1911) vol II, 627.

39 Baker, above n 30, 76.

40 Ibid 508.

41 Plucknett, above n 28, 121.

42 Baker, above n 30, 508.

43 Ibid.

44 Plucknett, above n 28, 122.

45 Baker, above n 30, 509.

46 Ibid.

47 (2016) 258 CLR 203.

48 See ibid [41] (French CJ).

49 (1985) 160 CLR 171.

50 Patton v United States (1930) 281 U.S. 276.

51 (1985) 160 CLR 171, 195 (Brennan J).

52 (2016) 258 CLR 203, [116] (Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ).

53 William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, (Oxford 1765-1769), vol IV, 308-310.

54 Baker, above n 30, 503.

55 Ibid.

56 Cited in ibid 504.

57 (1699) 12 Mod. Rep. 375.

58 See Blackstone, above n 53, 308, where Blackstone describes it as 'very little in use' and therefore 'treat[s] of it very briefly'.

59 Baker, above n 30, 505.

60 Christopher Corns, Public Prosecutions in Australia: Law Policy and Practice (Lawbook Co, 2014) 53.

61 Ibid 55.

62 Yue Ma, ‘Exploring the Origins of Public Prosecution’ (2008) 18(2) International Criminal Justice Review 190, 194.

63 Ibid.

64 Ibid.

65 Corns, above n 60, 55.

66 Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) ss 14, 49, 174.

67 Baker, above n 30, 509-511.

68 See generally Stephen, above n 8, vol 1, ch 12.

69 D M Byrne and J D Heydon, Cross on Evidence (Butterworths, 6th ed, 1986) 560.

70 Criminal Law Amendment Act 1883 (NSW) s 470; see also Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) s 405(I).

71 Crimes Legislation (Unsworn Evidence) Amendment Act 1994 (NSW).

72 Milsom, above n 1, 421.

73 Ibid.

74 Larceny Act 1861, which reflects the similar wording in the original act of 1757.

75 James Taylor, Boardroom Scandal: The Criminalization of Company Fraud in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Oxford University Press, 2013) 70-2.

76 The Joint Stock Companies Act (7 & 8 Vct. C 110), s 31 was in the following terms: 'if any such Director or other Officer of any Joint Stock Company registered under this Act wrongfully do or omit any Act, with Intent to defraud the Company or any Shareholder therein, or falsify or fraudulently mutilate or make any Erasure in the Books of Account or Books of Register, or any Document belonging to the Company, then such Director or Officer shall be deemed to be guilty of a Misdemeanour.'

77 Taylor, above n 75, 74.

78 Ibid 84-9.

79 Ibid 111.

80 Ibid 112.

81 Ibid 114.

82 Ibid 116.

83 W Clifford, ‘An Approach to Aboriginal Crimonology’ (1982) 15 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 3, 13.

84 Elizabeth Eggleston, Fear, Favour or Affection (ANU Press, 1976) 278.

85 Bruce Debelle, ‘Aboriginal Customary Law and the Common Law’ in Elliot Johnston, Martin Hinton and Daryle Rigney, Indigenous Australians and the Law (Routledge, 2nd ed, 2008) 85, 89-91.

86 Clifford, above n 83, 13.

87 Ibid 14.

88 Debelle, above n 85, 94.

89 R v Jack Congo Murrell (1836) 1 Legge (NSW) 72.

90 Debelle, above n 85, 94.

91 See, eg, Australian Law Reform Commission, ‘Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws’ (ALRC Report 31, 12 June 1986).

92 R v Nabegeyo [2014] NTCCA 4 at [16].

93 Magistrates Court Act 1989 (Vic) s 4E.

94 See NSW Government, ‘Youth Koori Court’ <http://www.childrenscourt.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Youth%20Koori%20Court%20A4_Accessib le.pdf>. le.pdf>.

95 See Criminal Procedure Regulation 2017 (NSW) Part 7.

96 G D Woods, A History of Criminal Law in New South Wales: The Colonial Period 1788-1900 (Federation Press, 2002) 21.

97 Ibid 22.

98 Ibid 26.

99 Ibid 25.

100 Ibid 30.

101 Ibid 40-1

102 Ibid 45.

103 Ibid 46.

104 Ibid 56.

105 See, eg, Balog v ICAC (1990) 169 CLR 625, [23].

106 Woods, above n 96, 58.

107 Australian Courts Act 1828 s 5.

108 Woods, above n 96, 63.

109 Ibid 64

110 Ibid 68-9.

111 Ibid 71.

112 Ibid 72.

113 Ibid 96.

114 Thalia Anthony and Craig Longman, ‘Blinded by the White: A Comparative Analysis of Jury Challenges on Racial Grounds’ (2017) 6(3) International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 25, 26.

115 Barry Wright, ‘Self-governing Codifications of English Criminal Law and Empire: The Queensland and Canadian Examples’ (2007) 26(1) The University of Queensland Law Journal 39.

116 Ibid 41.

117 Ibid 43.

118 Ibid 43.

119 Ibid 44.

120 Ibid 45.

121 Stella Tarrant, ‘Building Bridges in Australian criminal law: codification and common law’ (2013) 39(3) Monash University Law Review 838, 842

122 Ibid 58.

123 Tarrant, above n 121, 842.

124 Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) sch 1.

125 Criminal Code Act 1902 (WA) sch 1.

126 Criminal Code Act 1924 (Tas) sch 1.

127 Criminal Code Act 1983 (NT) sch 1.

128 Criminal Code Act 2002 (ACT).

129 Wood, above n 96, 345.

130 Crimes (Death Penalty Abolition) Act 1985 (NSW).

131 Crimes Legislation Amendment (Torture Prohibition and Death Penalty Abolition) Act 2010 (Cth) sch 2 cl 1.

132 Australian Parliament Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, ‘A world without the death penalty’ (Report, 5 May 2016) vii.

133 See generally Bernadette McSherry, ‘Constructing lack of consent’ in Patricia Easteal (ed), Balancing the Scales: Rape, Law Reform & Australian Culture (Federation Press, 1998) 26.

134 Crimes (Sexual Assault) Amendment Act 1981 (NSW).

135 See generally Terese Henning and Simon Bronitt, ‘Rape Victims on Trial: Regulating the use and abuse of sexual history evidence’ in Patricia Easteal (ed), Balancing the Scales: Rape, Law Reform & Australian Culture (Federation Press, 1998) 76.

136 Natalie Taylor, ‘Juror Attitudes and Biases in Sexual Assault Cases’ (2007) 344 Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice 1, 2.

137 Mary Heath, ‘Women and Criminal Law: Rape’ in Patricia Easteal (ed), Women and the Law in Australia (LexisNexis Butterworths, 2010) 88.

138 Victims Rights Act 1996 (NSW); Victims Compensation Act 1996 (NSW).

139 Kathy Laster and Edna Erez, ‘The Oprah Dilemma: The Use and Abuse of Victims’ in Duncan Chappell and Paul Wilson (eds), Crime and the Criminal Justice System in Australia: 2000 and beyond (Butterworths, 2000) 240, 244.

140 Fiona Manning and Gareth Grifith, ‘Victims’ Rights and Victims’ Compensation: Commentary on the Legislative Reform Package 1996’ (NSW Parliament, Briefing Paper No 12/96) 4.

141 Laster and Erez, above n 139, 253.