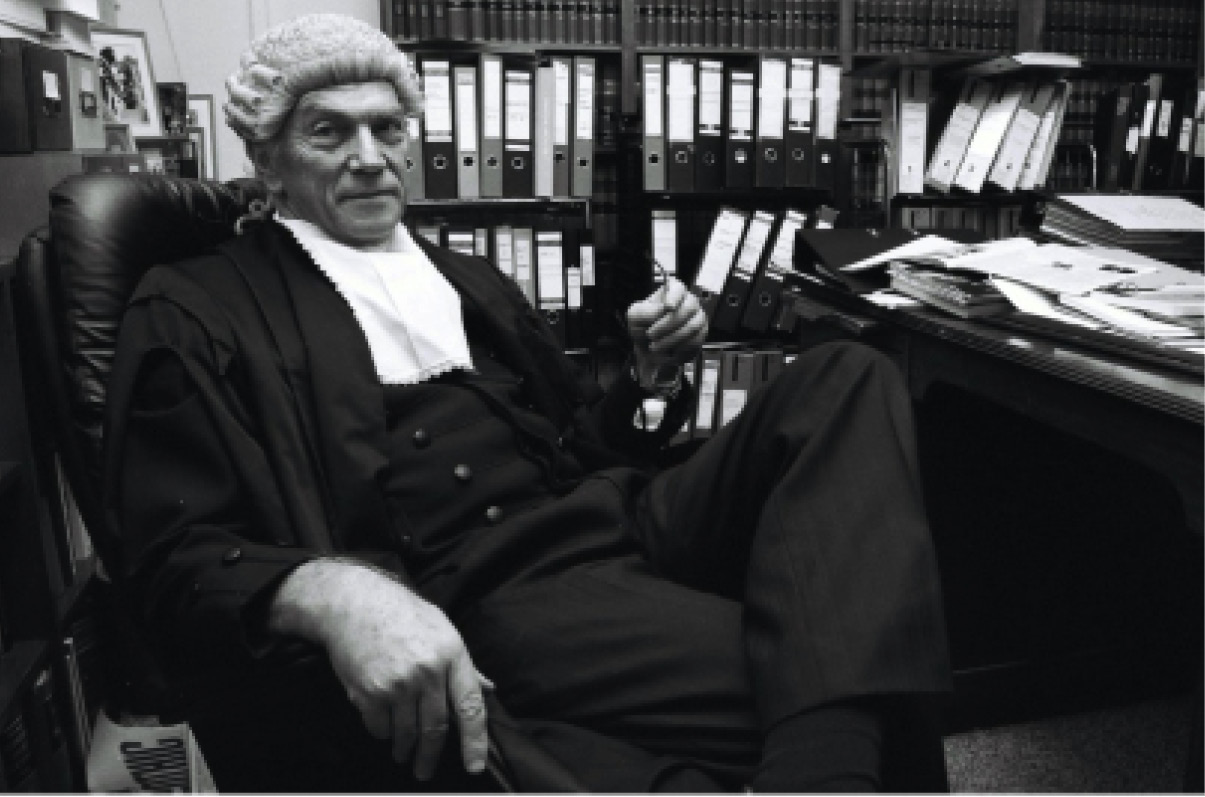

Chester Alexander Porter QC

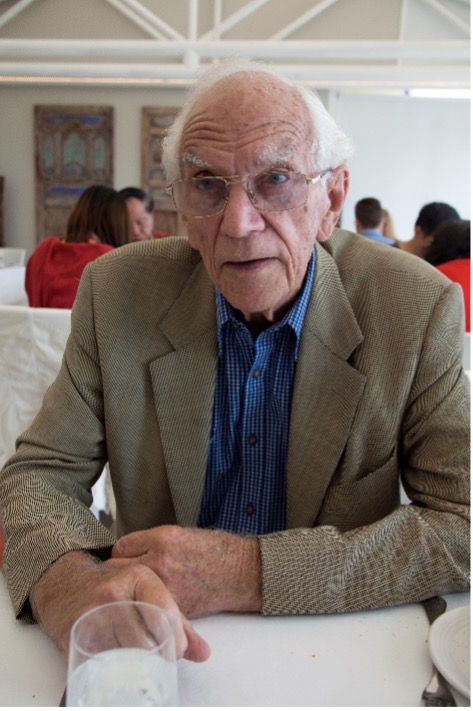

C hester Alexander Porter QC passed away on his 95th birthday last 15th March. Chester practised at the bar for 52 years, having commenced in 1948 aged 21 after doing law at Sydney University, the early part of which was during the war years. He was initially in the old Denman Chambers and in 1963 moved to the 12th floor of Selborne Chambers, where he formed many solid friendships and where he was the floor leader for many years. As a young barrister, he honed his oratory skills by joining Rostrum, where he eventually became a judge and mentor. Chester always described himself as a ’general practitioner’ who was open to accept any kind of brief, but he was probably best known for his work in criminal law and allied fields. Chester was undoubtedly the pre-eminent criminal law silk in Sydney for at least two generations of barristers. Numerous present judges and Senior Counsel were his juniors and untold numbers of them went to him over the years for advice and mentoring. He was a President of the Academy of Forensic Sciences and a President of the Australian Council of Professions.

Chester’s list of significant high-profile ca ses included:

- the 1951 Royal Commission into the murder conviction of Frederick McDermott

- the second Royal Commission into the 1984 sinking of HMAS Voyager

- the Royal Commission into the circumstances of the prosecution of Superintendent Harry ‘the Hat' Blackburn

- the inquiry into the conviction of Alexander McLeod Lindsay

- the 1976-78 Nagle Royal Commission into NSW Prisons

- representing the NSW Bar Association in the proceedings opposing the admission of Wendy Bacon

- appearing for the Minister of Environment in the 1992 ICAC inquiry into the circumstances of the appointment of Dr Metherill to a position in the public service

- the Royal Commission into the convictions of Lindy and Michael Chamberlain

- the trial of Judge John Foord

- one of the trials of former Detective Sgt Roge r Rogerson

- the trial of Andrew Kalajzich

Chester’s dedication to being a ‘general practitioner’ saw him doing criminal trials on both sides of the Bar table. After appointment as a Silk in 1974, he was involved in prosecuting some of the lengthy and complex trials arising from investigations by the recently formed Commonwealth-State Joint Drug Task Force. At the same time, he was becoming the senior counsel of choice for the defence.

Chester’s informal advice in criminal law matters was always of immense value. He hated the scattergun approach in which a defence counsel would go down every rabbit hole, just in case there was anything there. He thought that the best approach was to mount a defence with two or three really good points, and forget the other ones that would just dilute the good points. He would take on clients without any sort of moral judgment. When persons who didn’t understand the law asked him how he could represent guilty people, he would say to them 'As they enter my chambers, they take on a halo of innocence'. Such was his adherence to the presumption of innocence.

Chester was renowned for having an open-door policy in Chambers and anyone who entered his chambers would be given plenty of time and attention to sort out their legal problems. I was one of those very fortunate barristers to have benefited from Chester’s mentoring over many years. In a way, I was the son Chester never had, and I think he was delighted when I made the move to go to the Bar in 1977, thinking that I would become a commercial law barrister. At the end of my first year at the Bar I received a phone call from Gordon Beard, one of Chester’s long-standing solicitors, asking me whether I would accept a brief as Chester’s junior to represent a defendant in a legally aided, multi-accused committal proceeding in the Magistrates Court that was expected to go for three weeks. Having not yet had a hearing that had gone for longer than three days, I readily accepted. That committal became known as the ‘Greek Conspiracy case’, and it ended up going for three years, at the end of which I was a criminal law tragic. Chester never actually appeared in the committal proceedings, but I had the benefit of his wise advice during the whole hearing without him receiving any fees whatsoever.

I was not the only barrister whose career was powerfully influenced by Chester Porter. Many of his juniors progressed their careers by being involved with him as his junior in complex matters. Chester also assisted a number of barristers, whom I shall not name, who needed representation in their own right and who received not only sound representation and advice from him, but also much needed emotional support.

Chester was known at the Bar and in the media by two epithets: ‘Chester Porter walks on water’, which amused him, and ‘The smiling funnel web’ which he hated. Both had a foundation in reality. The first was based on his belief that extensive preparation was the key to success in the courtroom. The second derived from his cross-examinations, which could be withering, and his presence in court, which was commanding.

Chester retired from the Bar on 30 June 2000 at the age of 74 and after 52 years of distinguished practice. The Bar Association honoured him with life membership for his exceptional service to the law. For those who asked him, the excuse he gave for retiring at the peak of his abilities was that he couldn’t stand the idea of filling in GST returns for the government each quarter – an obligation that came into existence the day after his retirement. However, the real reason was that he wanted to leave while he was still at the peak of his craft and before the natural deteriorations of age set in. He had every encouragement from Jean for this step.

Chester’s family of origin was an interesting mixed bag. His mother, Coralie, was born Jewish, but totally rejected that background in her late teens and became a staunch Anglican. Chester and his brother, Hal, only found out about their mother’s exotic ancestry as adults when solicitor Cedric Symonds informed Chester that his maternal grandparents had been Jews. A confused Chester later spoke privately with his father, who confirmed the information and explained that Coralie had always wanted to keep it secret. Chester readily told his own daughters about their heritage, and they have always been proud of it. Daughter Dorothy discovered to her delight that one of their Jewish ancestors had been on Christopher Columbus’s famed expedition to the New World as an interpreter. Chester’s father, Frederick Porter, came from solid English stock. At a very early age, Chester was sent to boarding school at Barker College, which he found traumatic, due to the old school bullying mentality that was prevalent at the time. He later went to Shore, where life was better, but it was not really until University that Chester really excelled, graduating with first-class honours in 1947.

Jean was the great love of Chester’s life. Chester met Jean Featherstone through mutual friends. She was attracted by his intellect, integrity and good looks. He was attracted to her unassuming, giving nature, based on an immense inner strength, an intelligence that at least matched his own, albeit less demonstrative, a bubbly personality and her passion for her vocation as a science teacher. They were married in 1953. Their love, devotion and companionship endured until his recent death, with Jean providing him with unending support during the serious deterioration of his health in the last few months.

Chester and Jean began their married lives in a modest home at Mona Vale which they purchased very early in their marriage and which they lived in until moving together to a nursing home about a year prior to his passing. It was Chester’s love of animals that resulted in the purchase of a property in what was then a far-flung outlier of Sydney, and that was big enough for a serious hobby farm. Their home at Mona Vale consisted of three blocks on which Chester kept a menagerie of chooks, ducks, geese, bantams, and various other fauna such as native tortoises, as well as fruit trees. Anyone who came for a meal would be treated to roast duck which had been bred, slaughtered and dressed by Chester, and then wonderfully cooked by Jean.

Chester always valued his family life and made a point of never taking his professional work home. Considering the complexity of some of his briefs, that was an amazing achievement. His travel between Mona Vale and the city meant that he spent a lot of time in transit, so he would invariably leave home by 6:30 AM and return home at around 7 PM. However, once at Mona Vale, he would be totally focussed on life at home and his beloved hobby farm. Even after retirement, Chester and Jean could not break the long-standing habit of waking up at 5:30 AM.

In late 1983 Chester and Jean were involved in a horrific car accident on their way home from this writer’s place, when a drunk driver crossed onto the wrong side of Mona Vale Road. Chester, who remained fully conscious throughout, was severely injured, Jean less so, and one of Chester’s two cocker spaniels was killed. Chester spent months in hospital and rehabilitation, but insisted on returning to work even while limping and in pain. Surprisingly, he found that he no longer received prosecution briefs, but was even more favoured and in demand by defence clients. Chester put it down to solicitors and clients thinking that because he had suffered so much himself, he would have more compassion for their plight. Indeed, he thought he became a better advocate after the accident.

I was fortunate to have known Chester all of my life. Chester’s wife, Jean, was the best friend of my late mother, Ruth, and the three Porter daughters, Dorothy, Mary and Josie, were roughly of similar age to the three children in my own family of origin. Chester and Jean’s daughters became like close cousins to us. In 1962, my parents, Robert and Ruth, built a fibro holiday shack in the bush in the Blue Mountains, and a couple of years later Chester and Jean bought an old wooden cottage nearby. From then on, our holidays consisted of numerous bushwalks, picnics, birdwatching, horse riding, overnight stays, swimming in the council swimming pools and remote bush swimming holes, visits to the old picture theatre at Katoomba, dinners at obscure old-fashioned Blue Mountains cafes, Mark-rules cricket, bike riding on dirt roads, playing endless board games, and numerous other activities. For all six children in the two families, it was a wonderland for holidaying, and to this day we all cherish those years of holidays together. Chester and Jean were keen bushwalkers and birdwatchers, and we all derived from them a lifelong love of the bush and a knowledge of flora, fauna, geology and history of the mountains.

Chester had a great love of dogs, and cocker spaniels in particular. From an early age he always had a cocker spaniel, or two. His understanding of dogs and his ability to train them was one of the main reasons his daughter, Mary Davis, decided to study veterinary science, which led to her winning the University medal at Sydney University and becoming an enormously successful and proficient veterinary surgeon.

Chester also had a great love of history and literature. His interest in history and biography was deep and his general knowledge profound. There were very few topics on which he could not have a sophisticated and informed discussion. After his retirement, Chester and Jean became avid members of the Dickens Society. Their daughter, Dorothy Porter, began writing a diary and schoolgirl stories in her early teenage years. She went on to become a great poet and a teacher of creative writing. Her successes led to her becoming the pre-eminent Australian poet of her time, with publications galore, including probably her best-known work ‘The Monkeys Mask’ which became an HSC text. Unfortunately, in 2008 Dorothy passed away after a short illness at much too early an age of 54.

Mary was not the only daughter in that family to win a University medal. Chester and Jean’s youngest daughter, Dr Josie McSkimming, won the University medal in social work at UNSW and went on to become a highly successful clinical social worker in the mental health care industry, specialising in narrative therapy, couple therapy and clinical supervision of her fellow professionals, as well as lecturing generations of students at the same university. After many years of adherence to staunch Anglicanism, Josie became disenchanted with the institution’s attitude to women and, with her husband James, left the fold and wrote about her experiences in a doctoral thesis published as an insightful book ‘Leaving Christian Fundamentalism and the Reconstruction of Identity’.

Chester leaves behind his beloved wife, Jean; two of his three daughters, Mary and Josie; his daughters’ partners (Andrea Goldsmith, Bruce Sanderson and James McSkimming); five grandchildren (Kate, Tom, Sam, Alex and Emily); and four great-grandchildren (Elise, Abigail, Vera and Felix – the last born soon after Chester’s passing). He also leaves behind this writer’s admiration and gratitude for the huge contribution he made in so many diverse areas of my life.

Mark Tedeschi AM QC